To record or not to record, that is the question.

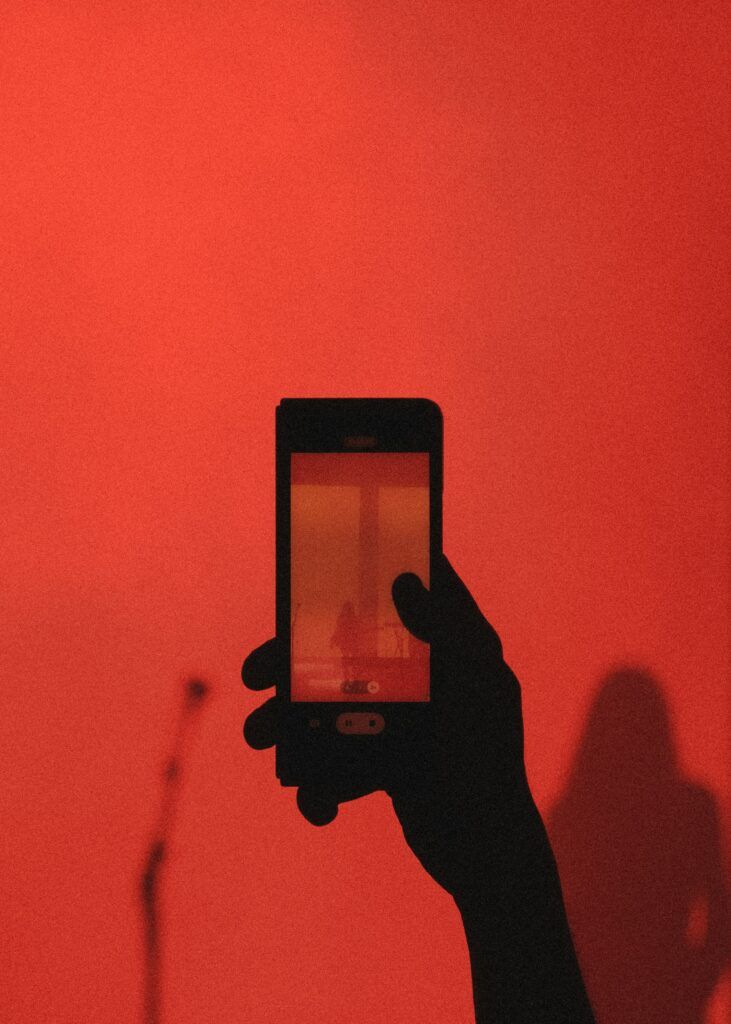

This year, we return to Sónar with a new project aimed at capturing the experience and emotions that festivals evoke, from the perspective of those who live them. We’ll explore the use of mobile phones as creative tools, challenging the perception that reduces them to a barrier between the experience and the present. The debate is open: some see phones as a nuisance, others as an extension of the body. We propose a third path — to use them with intention.

We return with a look that not only observes what happens on stage, but also what is breathed around. Because a festival is also a context, a climate, a contradiction.

Can the phone be something more than an annoyance at festivals? Are there ways of using it that don’t disrupt or unbalance the audience? Should we, perhaps, be more demanding and engaged as a crowd? Can a kind of empathy exist that allows artists and fans to enjoy the show, regardless of how one chooses to experience it?

This is not about romanticizing recording, nor about resigning ourselves to its omnipresence. It’s about exploring ways to integrate it without dissociation — without overshadowing the artists or those sharing the space — without replacing the experience, but adding layers to it. It’s about using it with awareness.

This article doesn’t answer those questions, but puts them on the table as part of an essential conversation and wake-up call. At the same time, it serves as a prelude to the project we’ll present at Sónar 2025 — this Junes 12, 13 and 15 — a documentation initiative in collaboration between South Plug and Tusk Content, created to explore, propose, and documenting culture in the local scene, Barcelona, in an international festival context and under the current context.

During the festival, guest directors Derevnin Oleksandr and Fedorov Denys will move freely through stages, filming exclusively with smartphones and custom lenses. The resulting pieces won’t aim to represent the festival, nor to offer a definitive version of what happened. They will be authorial works — fragments built from the perspective of the directors as audience and creators. A boundless exploration of the mobile phone, seeking to consolidate new ways of seeing and filming.

Derevnin Oleksandr is a Ukrainian colorist, post production specialist at Tonko Agency and a part of DOP duo. His craftsman’s background as a sneaker restorer and painter, and technical skillset of a software engineer, led to a deep desire of constant learning and searching new techniques in audiovisual industry. Oleksandr always works with lighting on set, and direct understanding of how it works helps him prepare the foundation to achieve the desired result during the post production process together with Tonko Agency team and his co-DOP.

Fedorov Denys is a Ukrainian director, founder of Tonko Agency – a full circle production company based in Barcelona. His passion for cinema, contrasts and dark humor is what builds his works – commercials, documentaries and international award-winning short films. Denys moved to Barcelona with his family 3 years ago and built a small team of passionate creators from Ukraine who make big things and work with Barcelona’s local creative community to blend another cultural vision and present a different workflow.

Choosing the smartphone as a tool is neither anecdotal nor aesthetic — it’s a statement. In a moment where screens divide opinion, this proposal aims to reclaim their use. Not recording out of habit, but with intention. Turning the automatic act into a narrative, sensitive gesture. Without losing sight of others. Without ceasing to be present.

This project doesn’t aim to resolve the tension between presence and recording — it inhabits it. Because looking is also a form of participating. And recording — even with a camera that fits in your pocket — can be a personal gaze, a subtle authorship, and a way of truly experiencing. The resulting works won’t offer answers. They’ll be questions in the form of images. That’s their strength.

Sónar continues to be a space of encounter, risk and celebration. The 2025 edition arrives with an ambitious and diverse lineup: from key figures of experimental electronica like Actress & Suzanne Ciani, Alva Noto & Fennesz or Grand River & Abul Mogard, to rising talents like Wallis, Lucient and p-rallel b2b Tommy Gold, who bring new nuances to the festival’s sound ecosystem.

The nights will bring unexpected crossovers like Skrillex b2b Blawan or Skee Mask b2b Actress, while the day will be loaded with sensory immersion, expansive visuals and sets that challenge the limits of the club, with artists like DJ Heartstring, Ewan McVicar, AEREA and MCR-T.

At Sónar+D, the focus will be on the relationship between art and technology, with talks, shows and interactive experiences on artificial intelligence, bodies and music, by projects such as AudioStellar, Synapticon, Eat My Multiverse or Lemongrass & Bass.

This year, the debate was not initiated by a work. It was triggered by socio-political conflicts -related to Sónar and KKR– and the absence of artists. The removal of Arca and Kode9 (and more than 20 others) from the lineup not only changed the programming, but also sparked a conversation that was already simmering: what does it mean for a festival with a progressive discourse to be, at least in part, financed by a fund like KKR?

Criticism points to a clash between narrative and infrastructure. For years, Sónar has been a symbol of innovation, diversity, and critical thought. How can that identity be upheld when its financial backing comes from systems that actively repress those very values?

The conversation is now public — not just on social media, but also in media outlets and within the artistic community. Some defend the idea that culture cannot depend on the moral purity of its investors, that what matters is what happens on stage, not who foots the bill. Others argue that accepting certain funds is, even indirectly, endorsing practices that contradict the very essence of the art.

This conflict exposes a rift that goes beyond Sónar. It’s a broader discussion about art, capital, and ethics. About whether it’s possible — or even desirable — to separate the work from the system that enables it. And while there are no easy answers, one thing is clear: silence is no longer an option.

In the midst of this storm, with divided feelings from both audience and artists, complex but predictable, we go with the mission to observe and record. To intervene by expressing the context and participating in the archival record. To see what happens to the audience when they dance, when you interact, when they decide to use their mobile and how the context influences the reality of a festival at the moment it is lived.

We find it problematic that the burden of exposing and confronting these tensions so often falls on artists and their communities. Not because they lack voice or agency, but because others —producers, partners, decision-makers— should take responsibility before conflicts erupt publicly. When it’s always the same people who are left to call out the obvious, it becomes exhausting — and worse, it normalizes an unfair dynamic. We shouldn’t get used to that.

Our proposal seeks to inhabit the space with an open, receptive gaze. To bring into focus the tension between being and recording, between art and politics, between the archive and the body. With or without answers, the will to shape a vision is clear.

In a time where everything is recorded but so little is truly seen, recording with intention is almost a radical act. This project is just that: an invitation to document without numbing, to participate without invading, to avoid choosing between watching or filming — and instead, ask ourselves why we do it, and how we might do it better. The problem begins and ends with us.

See you outside.

And turn down your screen brightness.